Having recently finished George Kay’s caper Netflix series Lupin, I was blown away at the intricate adaptation (and expansion) of Maurice LeBlanc’s adamant gentleman burgler, Arsene Lupin. Equally as amazing was Omar Sy’s magnetic, multidimensional character Assane Diop comprised of both heart and fine style. That said, the series has the right balance of humor, mystery, suspense and emotion that, as a viewer, I am always concerned with the state of Diop’s family as he seeks justice for his father’s framing. Later in Season 1, we are shown that the people involved in the framing are only human, with their flaws and subjectivity to higher powers as needed. In this way, Diop is able to sympathize with those who wronged him, but is never completely trusting of them.

The series itself begins with the theft of Queen Marie Antoinette’s – yes, that Marie Antoinette – diamond necklace from the Lourve. This same necklace is reputed to have been a cause of the French Revolution 232 years ago when Antoinette is said to have refused to pay for the commission of the necklace, which was meant for King Louis XV’s mistress. This is raised in modern times as Diop claims the necklace in a high-stakes auction to get the attention of the man responsible for his father’s death.

The angle later moves to Diop’s expert use of charisma, thievery, subterfuge and disguises to combat mastermind Hubert Pellegrini – a man well connected with the upper echelon and underworld in France – and enact vengeance for Babakar Diop’s imprisonment and later, death. The plot makes it clear that Babakar was set up, beginning with the supposed theft of aforementioned necklace, and pleading guilty in exchange for a lesser sentence. The Pellegrini patriarch however manipulated the chains of government to enforce strict imprisonment in fear of information leaking. Not unreasonable for a man with much to lose.

Yet Pellegrini is beyond a bumbling old man, as is the case with many crime movies. He is methodical, comprehensive, and just as sharp witted as Assane as he moves to alter and destroy evidence of his dirty dealings and compatriots to Diop’s cause. This results in Assane being reduced to having no evidence, his new friend and disgraced, legendary journalist Fabienne Bériot ending up dead in attempting to help Diop, and Diop’s only son Raoul taken hostage and vanished. All in a five-episode miniseries that wastes not a single minute nor line of dialogue.

With a plot and premise like this show based on a book of the same caliber, it begs the question on why theft, specifically elaborate heists to steal precious art and priceless books are so beholden and popular in Western media?

First, caper/heists, in the fictional scene at least, are put together with bounds of strategy and hard work. The execution of this strategy inevitably fires up the audience for the “heist of a century”. Narratives preaching of people who work hard are great; the backbone ideology of America itself is to lift yourself up “by the bootstraps” to achieve a state of solitary financial freedom, stitched through upward mobility and advancing social network by tax brackets. A clean approach. Yet, to read, hear and watch stories about a band of misfits with varied skills, backgrounds and desires who work hard together to meet a goal creates a feeling of camaraderie between the characters and the viewer. I am reminded off the bat of Shawshank Redemption. While it was not a heist movie, it was a movie centered around the lives of two very opposite men, with families and dreams to return to. Ocean’s 11 is another great example; it went over well in the Rat Pack and 2001 days because of its unique characters, witty banter, engaging dialogue and overall execution and delivery, but it would not survive were it not for the band of characters involved. A heist film depends heavily on all of its members playing a part and having a motive.

Heist films and television shows allow us the opportunity to get crazy in the mind, to imagine how we would take on a laser, lock and getaway scenario. We do not walk into a movie immediately considering the repercussions of such a grand heist (unless we are naturally attuned to forming a critique). We are instead treated to a fantasy rooted in an exaggerated reality just for a brief moment of the day, to watch the highly suave art of outsmarting and manipulation of others, and to take the side of the thieves because they are that damn engaging.

The heist genre does not exactly inspire us to rob a bank or slither like a snake through museum defense systems, and if they do… please make that into a work of fiction. Rather, these films come packed with a sense of urgency, endangerment, and intensity when faced with the consequences, almost as though condoning a battle between our Id and Superego via Freudian speak. It is make or break, and no one can afford to fail, though 90% of the time the movie begins with a failed heist and one potentially insane character fresh out of the clink. Romanticizing the art of the heist is absolutely not the point of this writing; these stories allow us to empathize with a character of the six-to-eight and imagine what we would do in their shoes. Ambition, intellect, talents, work ethic are traits everyone possesses, at different stages in life, in different magnitudes and yet the story places all of these rare traits at the forefront of the film to explain the rush that comes with conquest. These traits however are meant to be used not at the expense of others but for one’s satisfaction.

FUN is dripped into the story at consistent paces. Most of us – me – would jump at the chance to lead and execute a complex plan for the take of a lifetime. Most would imagine which friends or allies they would call upon to assist, and feel inspired in some inexplicable way. If a band of misfits with ten years of radio silence between them convene and put their skill to the test to steal from the big boss man, that is a story worth telling. These characters – drawing back to Lupin are the embodiment of what we would like to embrace in ourselves. It is okay to be a little cold and calculating, to dream big and have audacious plans for a disgusting amount of wealth, and to be brave in the heat of a potentially dangerous confrontation. To be within the realm of possibility without risk, just for those two or three hours, is a beautiful, invigorating feeling indeed.

There is a formula of eight (8) keys that each great heist movie and book follows – for this I am thinking of Richard Stark’s The Hunter and Michael Crichton’s The Great Train Robbery:

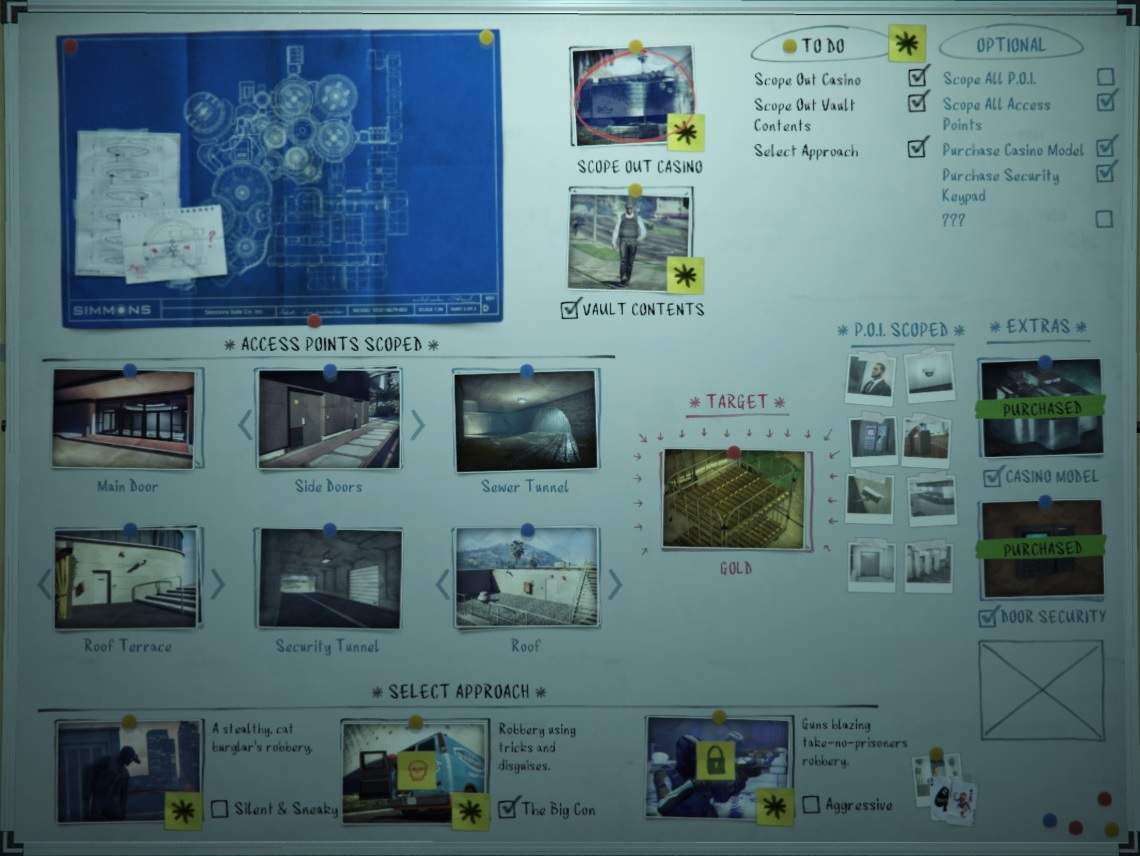

- The Stages of the Heist

- Each great heist in literature and film have a planning stage, an execution state, and the grand getaway. Inevitably one of these three will be hilariously – or tragically – flawed to create a rift in the story that must be patched. That said, without all three, the story will fail. Good stories like this spread the time between and on the stages unevenly, perhaps to focus on the cast or the set. We care about the characters whose name we have come to know, see the story to completion.

- The Risks

- A heist which goes off without a hitch is not going to be very engaging. The very real risk of imprisonment, harm to oneself or their family or failure keeps a story going. The flaws are what create a concoction of chaos and ad-libbed moments make up the realest moments in the heat of the moment. Keep the hiccups littered throughout the story rather than in one place.

- How fascinated would one be watching a bank heist that is pulled off perfectly? There are two ways this can be done vividly and flawlessly: if the heist happens as a flashback or when it happens in the climax of the movie. This latter stage is especially when viewers and listeners are rooting for the cast, regardless of their moral compass.

- The Team

- Easily my favorite part of the heist. Characters from all walks of life come together to see a plan through. Ideally, the relationships between each of the characters will be complex and they should not relate to one another. Polar opposites work well, so long as their differences do not crush the plan.

- The Motive

- Money is often the goal in caper films, and is why the story sometimes falls flat. We know already that it is a get rich quick scheme, but the question of why remains. Getting rich through a heist is a result, not a goal. Richard Stark’s The Hunter also offers a dated, but good example of this. Parker goes to beyond ridiculous depths to take revenge and in the process pisses of some major players in the Mafia. All of this to regain a small amount of money in a loss that left him screwed.

- Heists involve cash, and on the occasion an art piece to be sold. However I enjoy seeing a reason beyond the cash that is not cliche. Even if the reason is not relatable, the character should bust their behinds in pursuit of it. Parker’s incredibly petty heist over a pittance is forgiven through his vanity and irrationality from standing on principle. It is his money he is reclaiming, he owes no one an explanation. Cash serves as motivation, but often the cash is meant for someone else, less often it is for one’s selfish desire.

- Reading a story about a grand heist on the Lourve for little Alexander’s school program or to keep a house will lose me as a viewer. When the undertaking of a heist involves hurting someone close to you, then it becomes engaging enough to wonder why. Parker’s point of pride stands as a brilliant example, he has something to prove to himself, damn the expense, whether or not his motives are sound.

- The Belief

- As the audience, we are expected to root for the bad guy; they are the protagonist, after all! When the aforementioned factors are involved, you forget the societal conscious belief that theft is wrong. Even better when the cast are funny and likable people with questionable pasts. The target themselves are irrelevant. A fascinating story angle could be to see through the eyes of the victim for the movie, and offer a reason to band against the thieves.

- Simply put, if the thieves or the victim are bland, the story itself falls apart.

- The Outlandish

- What separates the heist genre from an egregious theft? What raises the stakes?

- The insane. Hanging from a wire inches from an alarm, the beads of sweat threatening to end your career leaves high tension. Scouting for a getaway car to find the least intimidating or likely option also gives this atmosphere: would you really suspect a VW Beetle to be a high speed getaway car? Maybe after it unfolds to reveal next-gen technology. Those strange moments give the scene life.

- The Plausibility

- Heists are not meant to be realistic. That should not be the chief goal. That said, heists, like sci-fi stories must be plausible, when impossible.

- Is the story believable? If it is, the story can progress. Yeah, I can see one using black spray paint on cameras to disable them. I am more likely to believe robbers who sound like they know what they are talking about, compared to the millions of pretend, run of the mill thieves out there.

- Is the story probable? It is not very probable that one man can carry 40 bricks of gold in one bag, those bricks are almost 28 pounds. But I could buy four men dividing the bricks among themselves.

- Plausibility lands somewhere in between. The right set of people and advanced enough skill, plausible happens.

- The Rules

- How the rules are broken matter. There is a different between gentleman burglars, expert thieves, and savages with fertilizer and nitrate.

The heist is an old favorite of mine, and watching it unfold in the 21st century in a suave way like Lupin, easily checks off what makes for a good heist. It had all the makings of a classic LeBlanc: a perfectly organized, bloodless theft with style. There is a sense of empathy and understanding for those looking to topple the order of a country, if by committing a crime that harms no one.

The French in particular are fond of a thief who does not kill, thus the creation of Arsene Lupin, Gentleman Burglar. To act without a weapon, without malice, targets a poorly defended public space and dupes the security with suave tenebrosity while speaking with manners, is a classic French story. And forever a favorite of mine.

Rooted in reality, what are the chances of art heists drawing a profit? We will talk about the art theft ring and profits next time!

-N

References

De Palma, Brian. Mission: Impossible. Paramount Pictures, 1996.

Stark, Richard. The Hunter. Doubleday. NY: New York. 1962. Print.