Reading is a basic literacy skill, yet agonizing to conjure concentration for it. It is difficult if for no other reason than the text existing in the past, with references and signposts unknown to you and therefore opaque and complex. There is no guarantee we will understand the author’s intend either, let alone the deeper meaning. I think often of Toni Morrison and Franz Kafka’s works’ baked heavy with subliminality and shaken aspects of society not easily confronted.

One example I can think of is scripture: whether one is openly critical or faithfully devoted to the words, there is a common string of concepts and language that suffocate the text if only to appeal to the readers’ understanding of the topic. There is no appeal to the author’s social background or environment to better associate with their reader. When a reader pursues the author for meaning, if they are able to derermine the background the author has developed for the text, there is no guarantee of comprehension, relatability, or that an author understands what they have created or what it will mean to readers. It is a double-blind study, sometimes with beautiful or disasterous results.

Today’s environment and its gearing toward online platforms puts the text in critical danger. Gone are the days of oxidized pages in tethered books with roundtable discussions (pandemic vibes exasperate this). We end up with situations that Gilles Deleuze describes in The Logic of Sense as “the schizophrenic and the little girl” both of whom undergo a phenomenological, transitory experience. The little girl, much like Alice in Wonderland and the bizarre rabbithole, identifies the wider world around her as “thus” – such is life – observing the surface of what she encounters reveals that what she sees is what she gets. A very black and white dichotomy that things are as they are, not strictly to say there is no hidden meaning, but that there is no worth in seeking it out. This Alice – Deleuze argues – experiences her world as a “body without organs”; her senses are raw, a manner of speaking language without careful articulation or consideration from the linguistic rules of the language; a metaphor to say that she experiences the world in a primal state of making sound and feeling the environment than to produce a conscious effort to interact with and understand the world.

In contrast, the schizophrenic in their perception fills the sensory vacuum that Alice has created in her wake; schizophrenia in this context does not simply hear voices or hallucinate, but hears what does not exist. Deleuze’s handcrafted schizophrenic must fill the void not with common sense, but with anecdotes and narratives to familiarize with the unknown. A concept we experience as we encounter unknown locales, peoples, and concepts: the human mind will desperately connect the unknown with what it does know using sensory cues. The issue risen here, however, is that the organs attributed to the body are illusions!

Alice sees the text as a primal beating toward encountering; a text is simply too dense on a first reading to comprehend its nuances and euphemisms. Those who actively think about the text and wrench away its phrasing and imagery to reveal a truth do so almost naturally – it is a fantastically difficult skill to do – Alice will then signify the reader’s objective state of mind. The absolute mess that comes with rereading a sentence over and over until it is safe to move to the next page. A haphazard yet infinitely more fun approach a reader can take is that of the Deleuzean schizophrenic, speaking the meaning into the void and crafting a mold, filling that void with familiar ideas they are unaware are facets of their own unconscious mind. Alice intrinsically knows the text is dead, and appreciates the life it breathes objectively, the schizophrenic wants to communicate with the unknown and give it some meaning.

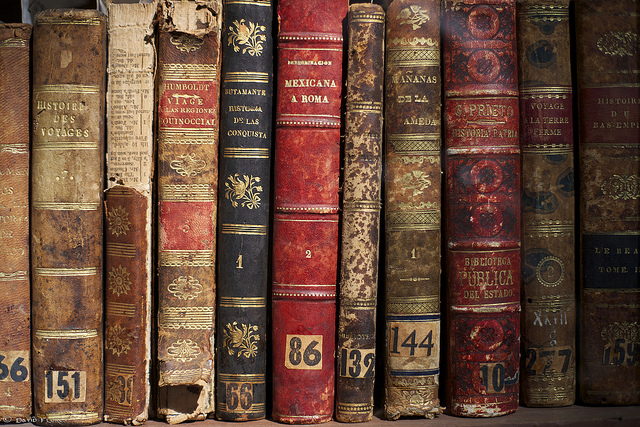

It stands to reason then that the act of reading can convey anything other than subjective meaning. It is equally difficult to explain a text objectively and subjectively without overlap. This is given more pressure due to the fact that if one were one ever living in a predominantly literary culture, that has since morphed into digital platforms; literacy rates thankfully continue to improve worldwide, and yet the very spirit of literature appears to be dying. Young upstart English, Classics, History and Philosophy buffs are acquainting with texts and forms that are ancient, antiquated, outdated or re-contextualized every year at an academic conference – our best friends in the majors are dead characters lost to time, immortalized in subjective interpretation until it is forgotten. The book has more heart than we think.

This is not to say that reading and literacy in a dense text are impossible; I quite enjoy reading so very much and have lately dipped into fiction for that comforting escapism glazed by imagery and sensory partnership, and I write frequently when I have time. Rather, I attempt to highlight here that reading is far more difficult than we presume only because it is a natural reflex to read and attempt to make meaning of everything we encounter – reading and writing themselves are ancient motor skills but are still only roughly 5000 years old compared to our 200,000 year old existence as a human being. There is much to be done. If the text is dead, unable to be revived, we must become a dedicated black arts specialist and raise it in such a special way that it becomes a conversation once more; I am reminded of my old PhD advisor’s comment that all PhD and original research are simply an already-done perspective, shifted one degree, and then someone builds upon that later when your research is found (assuming it ever is!). Reading can warp into a phenomenological act of metaphorical schizophrenia as we wrestle with meaning and sit on chairs and lie down wondering just what happened at the end of the book.

Reading and contemplation is a due process, and a long one, but a worthy venture. Homer’s Odyssey rings this bell; the Ten Year War was long, but the hardest journey was finding the way home; the home being our familiar, comfortable state of mind. It is hopeful as well, a true gamble that we can revive the text in our minds subjectively, then objectively discuss it with those around us in a two-step confrontation. That can be wrapped in a single word: Lazarus.

Reading, much like necromancy, as oxymoronic as it sounds, is simply difficult. There is much to appreciate about a natural yet incredibly complex behavior.

-N

References

Gilles Deleuze, The Logic of Sense, trans. Mark Lester, Charles Stivale, ed. Constantin V. Boundas (Columbia University Press, 1990)

Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology, trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak(Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013)