When the end of the world arrives, will you be ready?

An indeterminate amount of media and literature covers our impending doom, whether that be climate change, a supernova, aliens invading our earth and so on. The zombie, however, is noted to be a sudden onset of societal degradation. Their existence always provokes a catastrophe, society collapses and people are left cowering in some dank alley looking to avoid or pick off a shambler.

Pop culture and folklore has described the zombie as an undead corpse looking for braiiiinnns to a malevolent demonic entity seeking destruction. We have seen their presence on the big screens since we were young, from Michael Jackson’s classic “Thriller” to wildly popular AMC series The Walking Dead. Their existence represents a fearful, hyper-realistic unknown that has a possibility of occurring despite its improbability. Unlike most monsters, which are products of superstition, fear and religious counterrances, zombies exist on the basis of scientific fact. Their only mission is to feed and this urge is caused by their infection derived from many origins. Steven Schlozman’s pseudo medical analysis on George Romero’s conceptual Night of the Living Dead considers the zombie’s condition to be a very real possibility and established the condition as Ataxic Neurodegenerative Satiety Deficiency Syndrome caused by an earthbound infection and is spread airborne.

In movies, shows, video games and books, zombies are actualized by a freak accident, and the infection rampant in their veins are passed on through bites and exposure to bodily fluids. That is the baseline for what makes a zombie. From there, representations of the voracious corpses branch off and become semi-original beings with a wide variety of names (walkers, muertos, shamblers, Z’s, freakers, living dead, demons, undead, etc). Max Brook’s The Zombie Survival Guide lists the cause of the outbreak from a virus called “Solanum”, Resident Evil has its t-Virus, The Last of Us has its degenerative fungal Cordyceps Brain Infection, Night of the Living Dead has the virus caused by radiation from a NASA probe, and other media has the virus as a mutation of prions, measles, and rabies (Dying Light’s Harran Virus). A great zombie representation explains the virus’ origins, and how best to prevent exposure.

They arrived on the literature scene as far back as 1697, and hit the film scene with their monster peers Dracula and Frankenstein with the release of White Zombie in 1932. I am remembering Max Brook’s World War Z in how zombies were introduced. Seemingly everywhere, zombies appeared from nowhere and ambushed everyone in sight, the world fell into a panic, military order came into effect and society fell. Realistically, society would not collapse as long as there is proper damage control, which seems to have failed in this book. I digress.

The tragedy of the zombie seems to be in its implied motive. It does not reason, it does not speak, it does not ask, it only eats. The brain, specifically, depending on what media you are consuming.

Real-Time Strategy

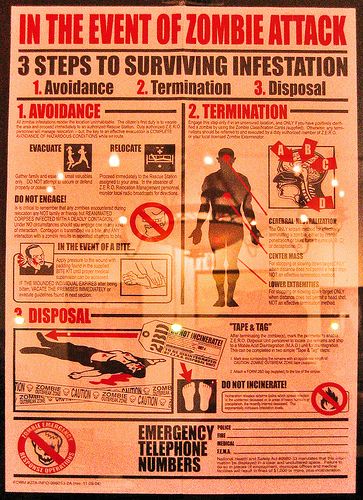

Considering a zombie apocalypse is a favorite topic discussion for many people. In my courses, I frequently toss scenarios for my students to consider and am always, always surprised at the answers I receive, given that their first priority is to secure housing or some weapon.

The heart is there; thinking about catastrophe and not having to face it gives a small surge of adrenaline, we are collectively bracing for things to come in a controlled environment. Disaster scenario teams are built in class: one team conceptualizes how the virus came into play, a second team attempts disaster control, and a third team creates a strategy for containing and treating the virus on a reasonable timescale. In modern America, thinking in absolutes creates our only working path to worst-case strategic analysis. Among my students, many of whom are freshman straight out of high school, this is a necessary team-building exercise to thinking critically, calmly assessing a situation, and testing their ability to plan, communicate with each other and respond to high-level content presentations.

This leads into a discussion on what makes the genre “horror” and we are left with three distinctions of fear: panic, revulsion, and dread.

- PANIC is fear through surprise. What makes a game or movie “scary” with adrenaline pumping and jumpscares to keep you on edge at night.

- REVULSION is fear through association. Zombies in literature and media are used as symbols of humans without humanity; we instinctively fear the idea of death coming to life since it is associated with a soulless, rotting corpse trying to eat us (which has its own history by the way – zombies don’t eat brains ‘just because’, they eat brains because we produce serotonin and dopamine, which make us happy and push through pain. They eat brains to eat the dopamine and have a temporary end to suffering.

- DREAD is the overall fear of the unknown. This is a Lovecraftian type of specialty and is the slowest-growing kind of fear. Something that makes us realize that something cannot be stopped or cannot be comprehended at any given time. It takes time to get over this kind of fear. An existential crisis is a good example: what happens to us after we die? Is there a god? Where did reality come from? In context, we might ask if zombies could ever be stopped (think of the Walking Dead where no matter what, even if you aren’t bitten, you will turn when you die).

Keeping Up Hopes: The Collective Therapy

In returning to World War Z, I ask myself how, and why, zombies are so insanely popular among us. Brooks’ work is a modern retelling and twist on the 80’s and late 90’s disaster management in many Western countries, but is therapeutic in its kinship; we would all collectively spaz out and consider options to save ourselves. Consciousness limits what we can see, and causes us to come together in a tribal faction to better understand our surroundings, though realistically, outbreaks would take many months to span the nation, and during harsher seasons like winter or summer, zombies would die out quickly.

We are encouraged by that fact, to live in denial of threats that could quell us, and for ruling establishments, keeping the general people oblivious to the catastrophe at their doosteps ensures no mass hysteria… which never works. Transparency always seems to be the best option in fiction for coordinating a plan with the general populous, but the truth is always shared far too late, 1984 style. The zombie outbreak, if we look in reality, may never be televised not because it would cause a riot, but because it would highlight the shortcomings of the governments response.

The beginning of World War Z elaborates: despite the U.S. government’s awareness of the plague, lack of decisive action – and bickering between policymakers – caused the sudden outbreaks. As Grover Carlson , fuel collector notes, the government in the book has fallen to fantastic case of he said, she said and did not properly respond to the Warbrunn-Knight threat assessment:

What, you would rather we told people the truth? That it wasn’t a new strain of rabies but a mysterious uber-plague that reanimated the dead? Can you imagine the panic that would have happened: the protest, the riots, the billions in damage to private property? Can you imagine all those wet-pants senators who would have brought the government to a standstill … can you imagine the damage it would have done to that administration’s political capital?

Brooks, World War Z (2006), Grover Carlson’s Interview

Would this imply that consciousness is managed by the collective elite to manipulate what can see? Yes, but they cannot control every aspect of society when government response has failed.

Apocalyptic literature and the rise of the zombie go hand in hand, because we have learned to manage oncoming disaster in our minds, by living out the days of fear, famine, fire and frost in tales that are within the realm of possibility. The zombie is an eternal fixture in literature. We are made to fear them due to their constant state of aggression and inability to reason. We hate them because they destroy. We run from them to protect ourselves. Brooks asks a heavy question: why is there such a sudden and ravenous fascination with ghouls?

Because they are simple to understand. Because the simplicity of primal fear is the appeal of the zombie. They don’t have complex motivations, they do not have a goal, they do not have an establishing character arc. They seek out the living and eat the. Kill them, run from them or they kill you, much like humanity before the rise of civilization, and nature in its current state.

The seemingly everlasting state of anxiety from self-preservation has made the zombie a lauded and desired form of fiction, precisely because it is closer to reality than other monsters in the world. Yet that is exactly what World War Z and the zombie genre in games, films and other media capture: we die when we give up hope. The biggest threat in a crisis is not the external force, but the collapse of the internal structure that keeps us together.

Readying the Worst-Case Scenario: The Zombie as Revitalization

As per subtitle, the zombie genre reminds us that we are mortal. We are mortals, with finite lives and are susceptible to dying at any moment for any asinine reason, and that is what the genre offers: real strategic analysis. The novel is a masterclass on visual entertainment and a lesson in net assessment: identifying reality in a tsunami of hope and fear is no easy task, because how do we assess the unthinkable? How do we plan for an unknown entity or even that leads to destruction? The crux of the novel is not about beating the zombies – they will always exist – the driving force of the novel speaks to our nature, to adapt and adjust to reality as it comes.

Brooks criticizes the means of U.S. strategic thinking in the novel. Not winning a war since 1945, the war machine transitioning into the war economy, and a constant state of avoiding responsibility and enacting plausible deniability. This has created a war against the zombies with internal combustion; America fights the war it desires, on it’s own terms and controls the flow of battle. The titanic “Battle of Yonkers” in World War Z is a hallmark example of the American Way being destroyed:

Perfect name, “Shock and Awe“! But What if the enemy can’t be shocked and awed? Not just won’t, but biologically can’t! That’s what happened that day outside New York City, that’s the failure that almost lost us the whole damn war. Yonkers was supposed to be the day we restored confidence to the American people, instead we practically told them to kiss their ass goodbye.

Brooks, World War Z, Battle of Yonkers

The Battle of Yonkers was considered the biggest unmitigated implosion for the military and rattled the public’s confidence in them. Several thousand soldiers attempted to take traditional military battle methods into a war against 4 million+ walkers, and lost. Every Alpha Team in special forces, Air Force, Army and Marines were overwhelmed and killed, causing the “Great Panic”. The first error in judgment was to follow military instruction of targeting center mass (torso, because it cannot miss); only a headshot is known to kill a zombie. A secondary lapse in judgment came from the sheer amount of ammo required to combat them, which there was low supply. By far the most dangerous aspect of the war, however, was the lopsided morale: zombies have no need for morale, and basic military tactics to scare the enemy into surrender through Shock and Awe – a demonstration of weaponry and firepower – did not work. Where soldiers could be made afraid, a living corpse physically cannot become afraid from the lack of neurons and synapses. This created a constant, unending, terrifying advance that demoralized the soldiers instead. The zombie war caused the soldiers to fight how the zombies wanted, by exhausting their munitions and minds and flee.

The war taught the American armies the severity of their plight and the pressing need for communication. By the end of World War Z, the remaining population has long since cast away their narcissistic “strongest-in-the-world” mentality. In China, Russia, Japan and America everyone has instead resigned to survive as best they can now that the regions have been “liberated” and the zombie infestations cleared out from every major city. This is a hope spot for readers, it guides us through a didactic journey in self-preservation and community, but is realistic to demonstrate that societal peace does not come for free.

This genre is no game, and the zombie itself is almost never the main threat of the stories they occupy. In stripping civilization down to the bare essentials, society collapses and people turn on each other to survive. Our intricate daily nuances, the noise of social networks, political compromise, corporate hierarchy, conflicting identities, economic disparities, faceless terror threats and branded infotainment, they all fade into the dust, and we are left with only the simplest questions of how to survive. We are humbled in our tragedy, adjusted in our chaos. We learn, and the apocalyptic call of the zombie stands as a realistic, haunting favorite medium for that understanding.

The charm in the zombie genre, I argue, is that we cannot help but to see a great action scene, hear a guttural call of hunger and read a vivid extract and think, “what would I do, if that were me?”

-N